6th May 1953 – 6th May 2023

70 Years since the birth of the heart-lung machine

When US surgeon John Gibbon successfully closed an atrial septal defect in a 19-year-old girl on 6 May 1953 at the ‘Thomas Jefferson University Hospital’ in Philadelphia, using his heart-lung machine, the feasibility of open-heart surgery as a therapeutic technique was assured.

“Gibbon’s idea and its elaboration are now part of the gallery of achievements of the human mind, like the invention of the phonetic alphabet, the telephone or a Mozart symphony. Not a Deus ex machina, but a God machine’.

These were Eloesser’s words in his ‘Milestones in Chest Surgery’.

For millennia, man has thought of the heart as an inaccessible and inviolable organ. Aristotle himself, having seen it beating in the embryos of various animals posited it as the seat of the soul, the first organ to live and the last to die.

The progress of physiology in the seventeenth century and surgery in the nineteenth showed that its characteristics were in fact different: not the centre of the soul, but the centre of circulation, not a delicate organ, but an unexpectedly strong muscle.

The artificial heart-lung machine made it possible to exclude the heart from the circulation while still allowing perfusion of the rest of the organism.

In 1912, the great aviator Lindberg had imagined and conceived of an artificial heart, but only the strong determination of Dr. John H. Gibbon led to concrete results in this area in spite of the sarcasm, derision and disapproving judgement of his colleagues.

The idea of assisting circulation with an extra-corporeal blood circuit containing an artificial lung came to the young surgeon in 1935, after a long vigil at the bedside of a patient suffering from massive pulmonary embolism.

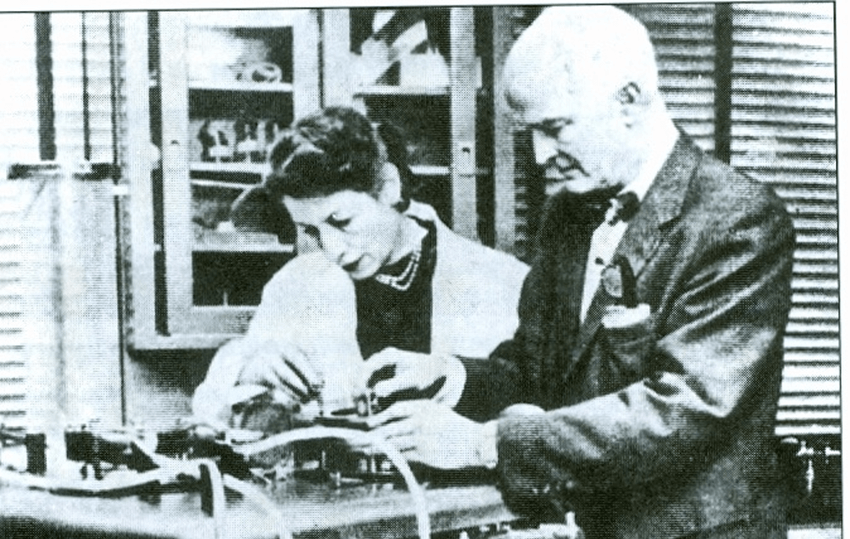

Gibbon, assisted by his wife Mary, designed and manufactured with his own hands the first device capable of replacing the function of the heart and lungs. The machine performed a double pumping of the left and right heart thanks to two roller pumps that compressed plastic tubes at a regular and rapid pace.

Gibbon designed an oxygenation system that mimicked that of the lungs by using a flat, stainless steel grid to distribute blood in a light film that could receive oxygen insufflations. He also imagined cannulas and aspirators for the blood spilled during the operations.

After two months, exactly on 6 May 1953, success came on a girl with an inter-atrial defect; her heart was cut out of circulation for about half an hour and replaced by the heart-lung machine.

Today we celebrate 70 years since the birth of the heart-lung machine.